Upwell Researcher Dr. Nicole "Nicki" Barbour is a movement and spatial ecologist. She received her PhD from the University of Maryland College of Environmental Sciences and is currently a postdoctoral researcher at SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry in New York. She is passionate about creating innovative conservation tools for endangered species on the move and is always looking for opportunities to collaborate and make her research available to the public.

When people think about researching animal behavior they often envision a scientist like Dr. Jane Goodall, using binoculars, scopes, and cameras, to observe primates engaged in behaviors like feeding, fighting and mating. So, what does a researcher studying animal behavior do when the animal takes off into the middle of the Pacific ocean? I study leatherback sea turtles, a highly migratory species that are found in every part of the world’s oceans except the Arctic and Antarctic. How could I find out more about what leatherbacks are doing once they disappear into the open ocean?

Luckily, Upwell Executive Director Dr. George Shillinger and colleagues had collected a dataset from 31 female leatherbacks who had been satellite tagged while nesting on beaches in Costa Rica. In addition to horizontal location, these tags recorded vertical data. As leatherbacks travel the ocean they regularly dive deep down into the water column to feed on sea jellies, avoid predators, thermoregulate, and navigate. The tags had recorded how deep the turtles dove and how long they stayed underwater.

Above: A visual representation of the data from a leatherback dive tag, with T = Time

These turtles dove thousands of times during the period they were tagged, so examining every single dive “by hand” would be incredibly time consuming. Instead, I worked with my colleague Dr. Alexander Robillard to create a machine learning model that could use a mathematical algorithm to identify patterns in the dive data and classify them by their shape. If you want to read more about the nitty gritty of this process, you can read our publication “Clustering and classification of vertical movement profiles for ecological inference of behavior.”

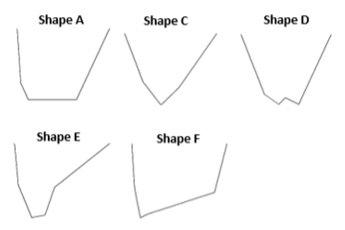

The shape of the turtle's dive was the key to understanding its behavior underwater. Our algorithm identified five dive shapes (shown below). Each of these shapes are associated with different kinds of behaviors such as searching for prey (Shapes A, E, and F), feeding (Shapes A, D, E, and F), traveling (Shapes A and C), cooling down by diving really deep (Shape C), and resting (Shape F).

After all the dives had been labeled, we wanted to find out which shapes were more likely to be deep dives or shallow dives, so we created another model called a “dynamic time warp model” that sorted dives based on their similarity to each other. This model made one cluster of deeper dives that was predominantly made up of shape C. These dives are generally associated with behaviors such as diving really deep to cool down (thermoregulation), searching for prey (jellyfish or gelatinous zooplankton) at depth during the daytime, and conserving energy by “gliding” on a dive.

Leatherback sea turtles follow sea jellies on their diurnal migration

The second cluster of shallower dives was made up mostly of Shapes E and F, which correspond to behaviors such as foraging or feeding near the ocean surface at night. This is because leatherback turtles feed on sea jellies that perform what is called a “diurnal vertical migration,”which means hiding from predators in deeper, darker water during the day and rising closer to the surface after the sun sets to feed on nutrients in the upper part of the water column. We were excited to find that our analysis confirmed that the leatherbacks in the study were following prey and other resources such as preferred water temperature, likely using a strategy called “vertical niche switching.”

Leatherbacks, especially the Eastern Pacific population, are critically endangered, and it is important to understand their behavior so that we can then create the best tools to save them. For example, we were able to use the data from this research to enhance the South Pacific TurtleWatch tool. This is a unique model created to empower fishers with the knowledge of where and when they are most likely to encounter leatherbacks in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, with the final aim to reduce the risk of incidental capture of turtles (bycatch) by fisheries.

If you are interested in reading more about how Upwell is mobilizing multidimensional movement data and fisheries effort data to help protect critically endangered East Pacific leatherback sea turtles, check out “Incorporating multidimensional behavior into a risk management tool for a critically endangered and migratory species” which was published in Conservation Biology.

Although working with data and algorithms may not be as exciting as my past experiences in the field, it is incredibly rewarding to use data analysis and coding to help conserve an amazing migratory and endangered species, such as the leatherback turtle. Thank you for reading, and you can take a dive into more information about my collaborative research efforts with Upwell and partners by clicking the links below.

You can find the published paper detailed in this blog with all results at: https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ecs2.4384

The manuscript was developed through a collaboration between several partners, including: Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, University of Maryland Department of Biology, Smithsonian Institution Office of the Chief Information Officer Data Science Lab, and Stanford University Hopkins Marine Station.You can also find a link to the machine learning model tool at: https://barb3800.github.io/TurtleDiveClassificationTool/

If you have any questions or want to learn more about this work, feel free to contact Dr. Barbour at her email: barbour@esf.edu.

Featured image of a leatherback sea turtle underwater by Juergen Freund

Dr. Heather Harris was invited to participate in the The Seattle Aquarium's Lightning Talk series in the session on sea turtles. During this Lightning Talk, five amazing speakers gave a five-minute presentation followed by a post-talk discussion answering audience questions.