Each year, thousands of mature female loggerhead sea turtles heave themselves up beaches in the Southeastern United States to nest, representing the largest loggerhead nesting aggregation in the world. In 2021, the state of Florida alone recorded more than 49,000 loggerhead sea turtle nests at index nesting beaches. Like all sea turtles, when the resulting neonate loggerheads emerge, they run a gauntlet of threats down the beach and through nearshore waters to begin an epic journey in the ocean.

Thus begins the cryptic life history phase known as the “Lost Years”. In the mid 1980s, famed sea turtle researcher Dr. Archie Carr published his theory that the loggerhead turtles found around the Azores must be part of the population that nests in the southeastern United States. Since that time, researchers, such as Drs. Alan Bolton, Helen Martins, Karen Bjorndal, Jeanette Wyneken, Kate Mansfield and others, have confirmed that Florida’s tiny loggerheads do, in fact, follow the Gulf Stream to the North Atlantic waters surrounding the Azores, a Portuguese archipelago approximately 1600 km from Portugal’s continental shores.

While we now understand that young loggerheads travel along currents, including the Gulf Stream and the Azores Current, little is known about what habitats they utilize, how long they stay around the Azores and where they go when they depart. Upwell recently partnered with the COSTA Project, Okeanos Center of the University of the Azores, Aquário de Porto Pim, Mercator Ocean International and Florida Atlantic University to unravel the mystery of loggerheads’ lost years in the North Atlantic Ocean.

Upwell’s Executive Director, Dr. George Shillinger, and Upwell Researcher Dr. Sean Williamson recently traveled to the Azores for the unique opportunity to satellite-tag juvenile loggerheads being rehabilitated at the Aquário Porto Pim before their release into the North Atlantic. Dr. Shillinger comments, “Upwell is committed to understanding the Lost Years life history period across different species and populations of sea turtles. Our work to apply these findings contributes towards improving conservation and management actions. We are so pleased to have the opportunity to form this unique collaboration in a region so important for the survival and trajectory of loggerhead sea turtles.”

Some of the tagged turtles were named for well-known sea turtle researchers. One was named after Dr. Alan Bolton. Another was named after Dr. Helen Martins (pictured here) who joined the team’s activities at the Aquário do Porto Pim. Yet another was named Peniche by the local police officer who found the turtle washed up on Faial and named it after his hometown on mainland Portugal.

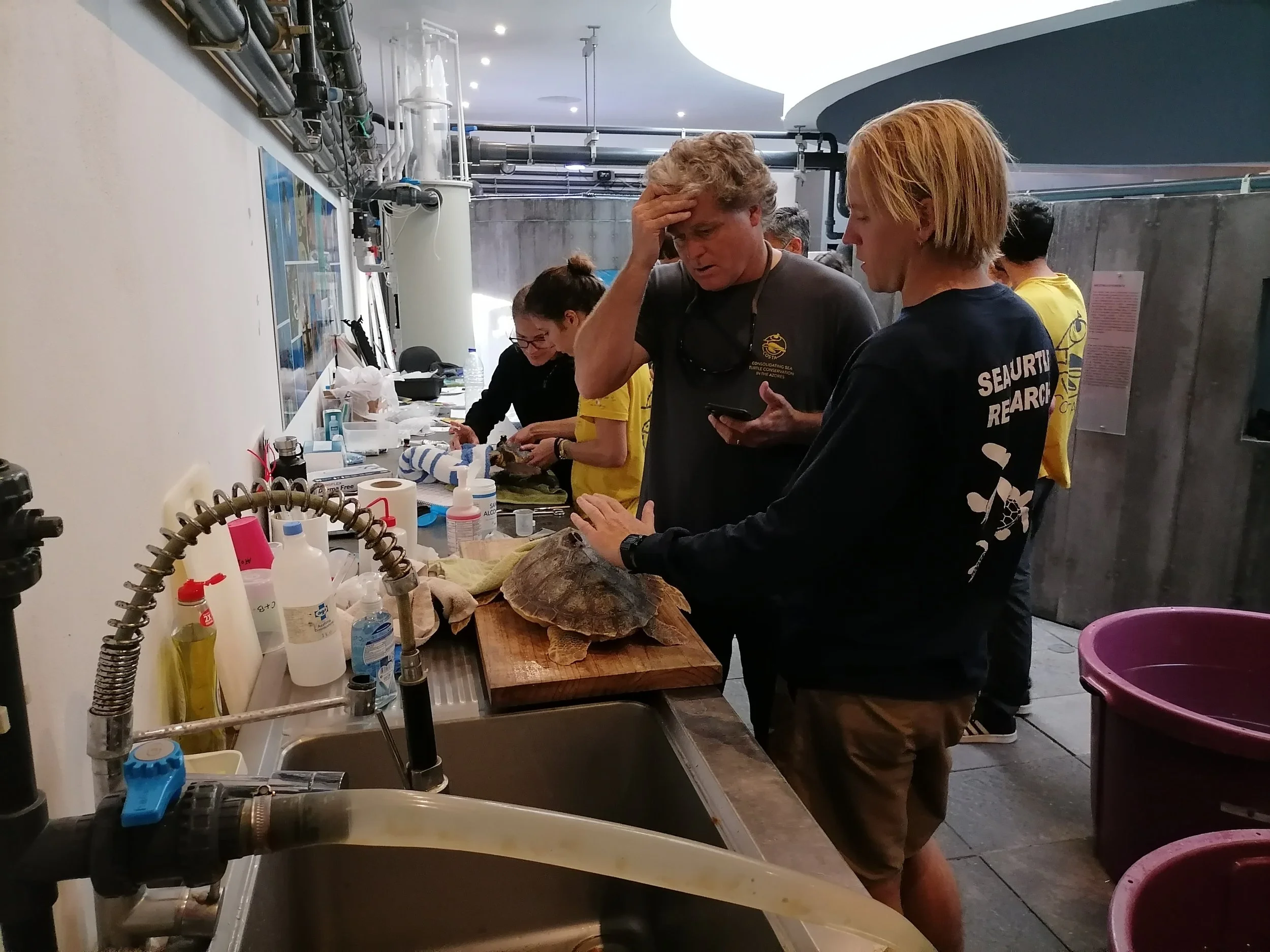

Photo: Drs. Sean Williamson, Frederic Vandeperre, Helen Martins and George Shillinger

Drs. Shillinger and Williamson worked alongside Dr. Frederic Vandeperre and other partners from the COSTA Project and the Okeanos Center of the University of the Azores to apply tiny prototype micro-satellite tags Lotek Wireless developed in partnership with Upwell. The six young loggerheads we outfitted with micro-satellite tags ranged in size from 0.3 to 5.5 kilograms, and, as with all satellite tags Upwell deploys on sea turtles, the micro-satellite tags are designed to shed naturally from the carapace as these loggerheads grow. Finding an ideal location in the waters between Faial and Pico, we released all six tagged turtles alongside a passive drifter. (Our research often uses passive drifters, which move with ocean currents, to approximate the direction the turtles would likely go were they not also actively swimming.)

Photo: Drs. Shillinger and Williamson of Upwell prepare a loggerhead for release. (Credit: João Lagoa)

Photo: Dr. Shillinger deploys the passive drifter (Credit: Nuno Vasco Rodrigues)

Photo: Juvenile loggerhead released at sea with a satellite tag (Credit: Nuno Vasco Rodrigues)

The advances in satellite tagging technology we are making with Lotek Wireless are allowing us a glimpse into the important early life histories of Northwest Atlantic loggerheads. Dr. Shillinger commented, “This is the most poorly understood life history phase for sea turtles, and only by increasing our understanding of where these turtles go and how they use their marine environment can we enact effective protections for them.”

For the first three weeks, all the tags continued to transmit, showing the majority of the turtles remaining in relatively warm waters heading in a northeasterly direction. All but one turtle followed trajectories distinct from the drifter, indicating active swimming rather than simply moving with the current. Three of the tags still continued to transmit position data two months after deployment, showing the loggerheads’ active swimming movements. (The drifter circled back to the islands, where it washed ashore.) Yielding several of the longest tracks ever recorded by these prototype micro-satellite tags, our research in the Azores is providing critical clues about loggerheads’ lost years in the Northwest Atlantic. Mercator Ocean International has been assisting with tag performance analyses, tag programming to optimize transmission success, and oceanographic modeling. Upwell is eager to continue unraveling the mysteries as we improve tag technologies and deepen partnerships in the region.

Maps: Tony Candela, Julien Temple-Boyer and Philippe Gaspar, Mercator Ocean International/Upwell

Cover photo: Nuno Vasco Rodrigues